According to an ancient Chinese saying “to get rich you have to build roads”. But what kind of richness do roads bring about? This is the riddle that in recent years has hassled the Afar clans living in Danakil, a 50,000 square kilometers (almost 10,000 under sea level) large region between the northern Ethiopian plateau and the Danakil alps chain along the Eritrean border. In this area, where people and animals are used to move at the slow pace of caravans along lava rock tracks and quicksand strips, in the last years China built hundreds of kilometers of paved highways. A revolution that is upsetting the fragile local balances.

Afar are Muslim nomad shepherds who make a living from herds put out to pasture in those arid regions. I meet them for the first time in the twinkling dust of Bati, a large livestock market along the way that from the Ethiopian plateau falls down in the direction of Semera and Asayta, respectively administrative county-seat of modern Danakil and ancient capital of a legendary sultanate. Oromo buyers – the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia, which is a considerable part of the population also in the southern part of the Afar region – touch the hips of frightened goats, test the fat humps of regal thin horned cows, go into long bargainings under a burning sun. On the contrary, Afar vendors show a calm attitude, keep a regal posture with a proud and even haughty glance. Wooden combs stuck into butter soaked hair, colored kefiah around thin necks, futa tied on spindly waists falling down to the ankles, inlaid sheath knives hanging along the hips. With their bushy heads of hair they look to me like people from the psychedelic Sixties.

Semera is a forced stop. The clumsy bureaucrats who are organizing contemporary Danakil have erected here a gigantic empty museum where visitors are supposed to cheat time waiting for entrance permits to “Pure Danakil”, as the northern part of the region is called. As soon as we get the papers necessary to continue our trip, the off-road vehicle leaves at full speed covering with dust this sad ghost town. We leave the road that goes on to Assab harbor in Eritrea and turn to mystic Asaiyta. When we reach our destination a full moon is just rising, looking at herself in the Awash river which stretches at the foot of the natural terrace on which the ancient capital of Afar nomads was built.

We set off at dawn, bound to Afrera lake, on another newly paved stretch of road winding through a striking desert of dried lava. After some tens kilometers a group of little boys come out of nowhere running on both sides of the road, flailing around and shouting. The driver on my side slows down, asks me for loaning one hundred birr (Ethiopian currency) and waits for the speediest boy to reach us. The money will be used to buy a 5 liter jug of vitamins enriched palm oil, a gift from the World Food Program to local families, which however do prefer traditional goat milk butter. Afar have never been in good relations with humanitarian help. In his “Dust of the Danakil”, Ian Mathie tells about a shipment sent to the local population by British cooperation during the famine that hit Ethiopia in the Seventies. While Afar people buried new victims each day, no one even thought of begging for help. Food remained for six months in a warehouse going rotten.

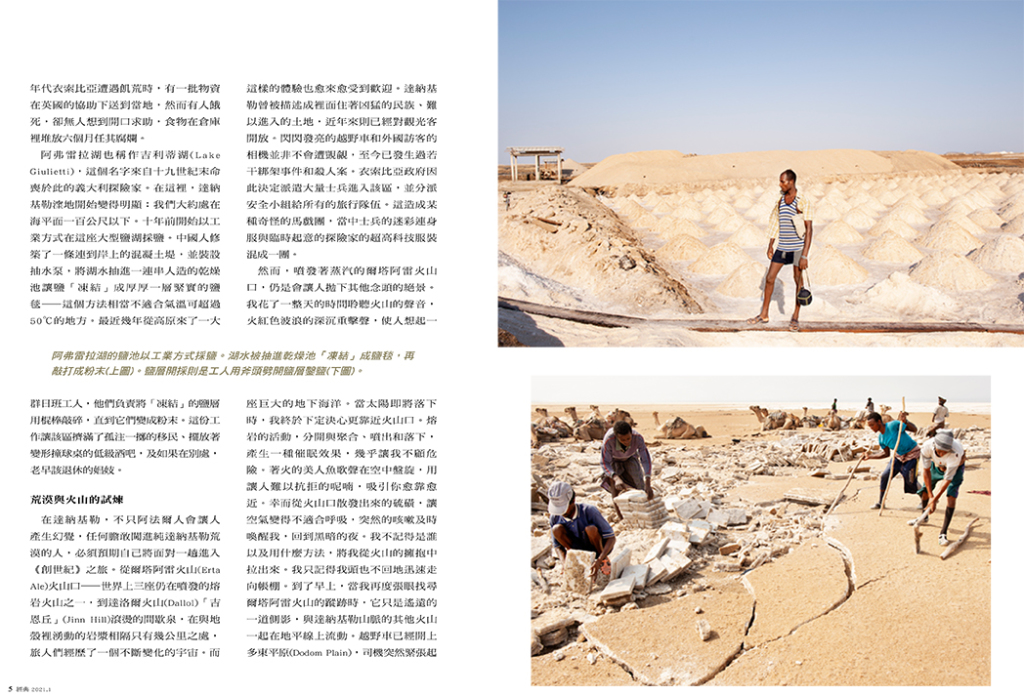

Lake Afrera is also known as lake Giulietti, from the name of the Italian explorer who died in these lands at the end of nineteenth century. Here Danakil depression starts to become outstanding: we are approximately one hundred meters below sea level. Over ten years ago industrial extraction of salt was started in this large salted lake. Chinese stretched a concrete strip up to the shore, where rough water absorbing pumps were installed. Lake waters are pumped into an immense streak of artificial desiccation basins, where salt is left “freeze” – a rather unfitting term for a place where temperatures can reach over 50 degrees – until it turns to a compact blanket. A crowd of day workers, arrived here in latest years from the plateau, crush the “frozen” surface with clubs until it becomes like dust. A business that has caused the area to be crowded by desperate settlers, barrelhouses with crooked billiard tables and prostitutes who elsewhere would have long retired.

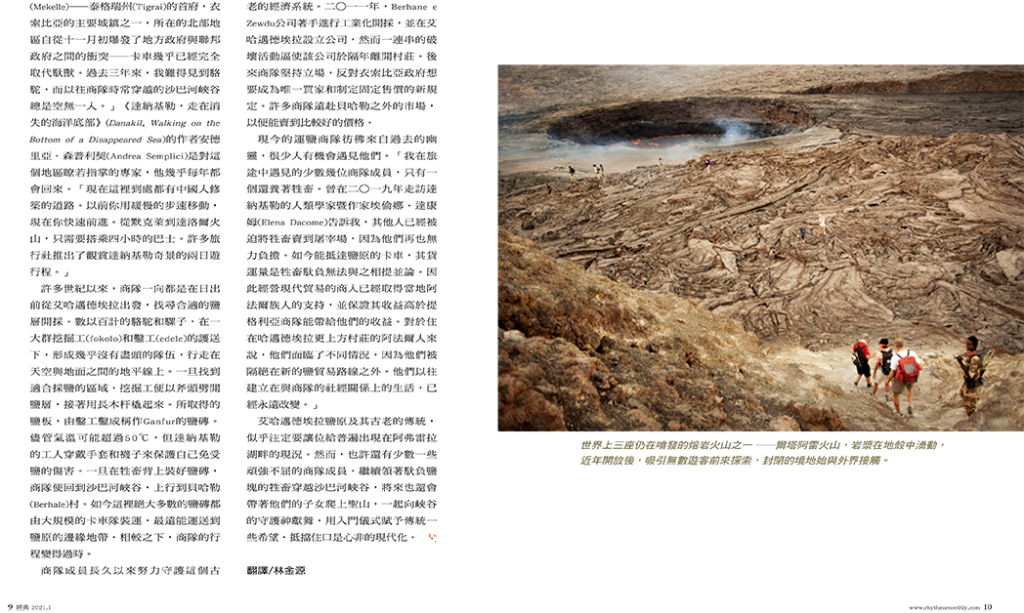

In Danakil not only Afar people are psychedelic. Anyone who ventures in Pure Danakil deserts must expect to face a journey into Genesis. From the mouth of Erta Ale – one out of three ongoing lava volcanoes in the world – to the scalding geysers in Dallol “Jinn Hill”, travellers go through a universe in constant metamorphosis stretched scarcely some kilometers above the pulsing magma of the Earth’s crust. An experience that is becoming more and more popular. Once described as an inaccessible land inhabited by fierce people, in recent years Danakil has opened up to tourism. The gleaming off-road vehicles and cameras of foreign visitors were not unnoticed. There have been kidnappings and some homicides. Ethiopian government has consequently decided to send plenty of soldiers to the area and assign security detail to all tourist convoys. This resulted in a sort of strange circus in which the soldiers mimetic coveralls blend with the ultra-technical clothes of extemporary adventurers.

The steaming mouth of Erta Ale, however, still is such an extraordinary sight to wipe out all other thoughts. I spend the whole day listening to the voice of the volcano, the deep pounding of the red-hot waves, the recall of an immense underground ocean. When the sun is near to sunset I finally make up my mind to move close to the caldera. The movements of the magma, which breaks and puts back together, gushes and sinks, produce an hypnotic effect that is near to exceeding my danger level. In the air hovers the singing of blazing mermaids that irresistibly whisper to get nearer and nearer. Luckily the sulphur exhaling from the caldera makes the air unbreathable and a sudden coughing wakes me up in time to move back to the dark night. I don’t remember who and how tore me away from the volcano’s embrace. I just remember that I walked swiftly to the tent without turning back. When the morning after my eyes looked for it again, Erta Ale was just a faraway profile flowing on the horizon in a line with the other Danakil ridge’s volcanoes. The off-road vehicle had taken the Dodom plain and the tension that had suddenly seized the driver didn’t leave space to nostalgia.

Dodom is an immense strip of sand stretched out among the Ethiopian plateau’s mountains, in the West, and Danakil volcanoes’ parade, in the East. Looking at the even surface on which our off-road vehicle is moving forward one might think that passing through the plain be just a kids play. Actually, we will have to wade across the rivers that from the plateau go into Danakil depression. We pass Ala and Dedemet with little problems, but we still have to go beyond the delta of Saba river, which is the most difficult and unpredictable. The plain is under a scorching sun, but in the distance alarming clouds hang over the plateau. We make a stop in the shadow of a group of palm trees to eat something. Some shepherds of the near Waideddo village take us the dagu (“rumors” as they are called in Danakil) that we feared: in the latest two days it has rained over the plateau and now the water is moving down along Saba dry riverbed. Soon the plain will become a dangerous marsh. We decide to leave immediately to travel along the thirty kilometers left to Ahmed Ela village without further stops. When we get there, our Afar guide tells me about the unlucky group of tourists which got stuck in the plain’s swamp for a week. When their supplies were over they had to walk under the sun as far as Ahmed Ela.

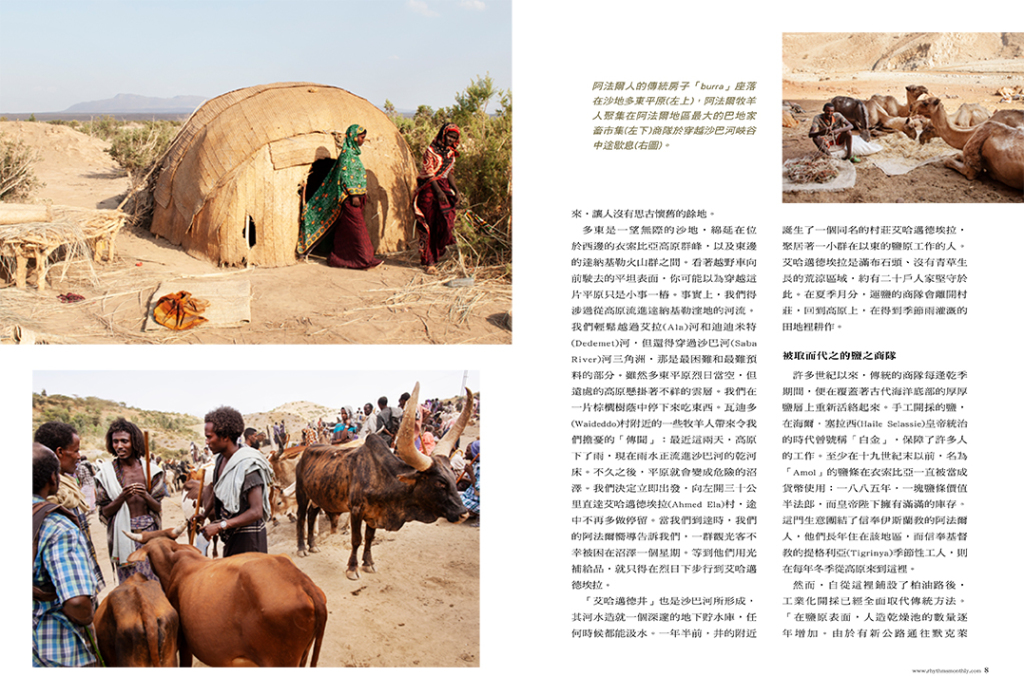

Also the “Ahmed well” is born by Saba river, whose waters have created here a deep underground reservoir from which it is always possible to draw water. About the well a village with the same name was born, populated six months a year by a small crowd of people working in the vast salt plain eastward. Ahmed Ela is just a desolate expanse of stones, where no grass grows. However, about twenty Afar families resist here also during summer months, when salt caravans leave the village to go back to the plateau to work in the fields irrigated by seasonal rains.

Through centuries the traditional caravans economy has thrived again each and every dry season on the thick salt crust covering the bottom of an ancient Ocean. Manual extraction and transportation of what by the times of Emperor Haile Selassie was called “white gold” – known as amolè, salt bars have been used in Ethiopia as currency at least till the end of the nineteenth century: in 1885 one salt bar was worth half French Franc and the Negus had storages full of them – guaranteed a job to hundreds of people. A business holding together Muslim Afar clans, who live in the region the whole year through, and Christian Tigrinian seasonal workers, moving here every winter from the plateau.

However, since asphalt roads have been spreading, even here industrial extraction has most completely replaced traditional methods. “In the salt plain the surface occupied by artificial desiccation basins is growing year by year. Thanks to the new highway to Mekelle – one of Ethiopia’s main towns, county-seat of Tigrai, the northern region where since the beginning of November an unsettling conflict broke out between regional and federal government, ndr – trucks have almost fully replaced animals. In the last three years I have hardly seen some camels and Saba river canyon, where caravans used to pass through, was always desert”. Author of Danakil, walking on the bottom of a disappeared sea (Terre di mezzo editore, 2012), the writer Andrea Semplici is a profound expert of this region, where he goes back almost every year. “By now there are Chinese-built roads all over the region. Where once you moved over at a slow pace, now you advance quickly. From Mekelle to Dallol it’s just a 4-hour bus trip. Many travel agencies offer two-days trips to see Danakil’s marvels”.

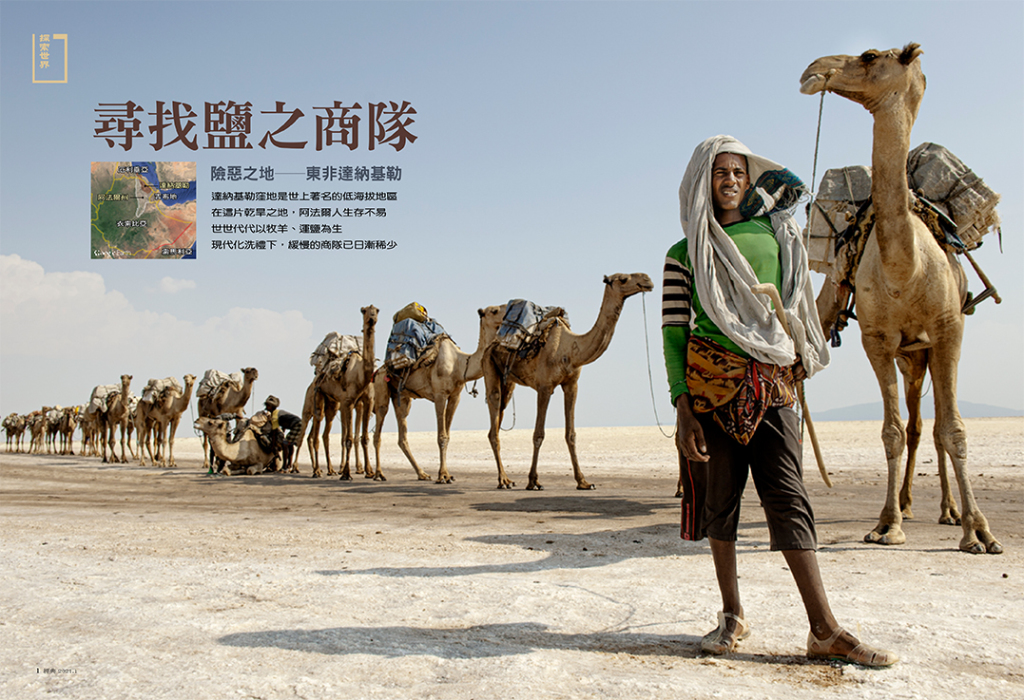

For centuries caravans have been moving from Ahmed Ela before dawn to find the right crusts to work on. Hundreds of camels and mules, convoyed by an army of fokolo (diggers) and edele (carvers), proceed in an almost endless row that marks the horizon between sky and earth. Once they find an area good for salt extracting, fokolo break the salt crust with axes, then lift it by long wooden rods. The slabs obtained are then chiseled by the edele to make tiles called ganfur. Despite the high temperatures, that can reach over 50 degrees, Danakil workers wear socks and gloves to protect from salt. Once ganfurs have been loaded on the animals’ backs, caravans go back Saba river’s canyon up to Berhale village. Here the majority of ganfurs are loaded on to the large-scale distribution trucks. The same means of transportation that today can reach the borders of the salt plain, thus making the caravans’ trip outdated.

Caravaneer have long strived for safeguarding this centuries-old economy. When in 2011 Berhane e Zewdu Plc engaged in launching industrial extraction and settling their business in Ahmed Ela, a series of sabotages compelled the company to leave the village the following year. Later on caravan people took position against the new rules wanted by the Ethiopian government, which aimed at being the sole buyer and set a fixed selling price. Many caravans reach beyond Berhale to market places where they are able to get better prices for their load.

Nowadays caravans may appear like ghosts from the past to those few who have the chance to meet them. “Just one out of the few caravaneers I ran into during my journey had kept his animals. The others – tells me the anthropologist and writer Elena Dak, who visited Danakil in 2019 – have been compelled to sell them to slaughterhouses since they could not any longer afford to keep them. Trucks that today reach the salt plain can transport unequaled quantities as compared to those that can be moved on animals’ backs. In this way those who manage modern trade have obtained the support of local Afar clans, to which they guarantee higher profits as compared to those they could get from Tigrinian caravaneers. The situation is different for the Afar people who live in the villages uphill of Ahmed Ela, who are cut off from the new salt commercial routes. Their life, which has been based on economic and social relationships with caravan people, has changed forever”.

Ahmed Ela salt plain and its centuries-old traditions seem to be doomed to give room to a situation similar to the one prevailing along Afrera lake shores. However, maybe some of the few tenacious caravan people, who still traverse Saba river canyon with their animals loaded with salt, will take their children up the Sacred Hill, where they will dance together in honor of the canyon’s guardian divinities. An initiation ceremony that feeds the hope for tradition to hold out against a forked tongue modernity.